import pandas

import geopandas

import xarray, rioxarray

import contextily

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt1 Spatial data

This block is all about understanding spatial data, both conceptually and practically. Before your fingers get on the keyboard, the following readings will help you get going and familiar with core ideas:

Chapter 1 of the GDS Book (Rey, Arribas-Bel, and Wolf forthcoming), which provides a conceptual overview of representing Geography in data.

Chapter 3 of the GDS Book (Rey, Arribas-Bel, and Wolf forthcoming), a sister chapter with a more applied perspective on how concepts are implemented in computer data structures.

Additionally, parts of this block are based and sourced from Chapters 2, 3 and 4 from the on-line course “A course in Geographic Data Science”, by Dr Elisabetta Pietrostefani and Dr Carmen Cabrera-Arnau (Pietrostefani and Cabrera-Arnau 2024). This course also provides code in R.

1.1 Packages and modules

1.2 Data

If you want to read more about the data sources behind this dataset, head to the Datasets section.

1.2.1 Points

Assuming you have the file locally on the path ../data/:

pts = geopandas.read_file("../data/madrid_abb.gpkg")Sometimes, points are provided as separate columns in an otherwise non-spatial table. For example imagine we have an object cols with a column named X for longitude and Y for latitude. Then, we can convert those into proper geometries by running pts = geopandas.GeoSeries( geopandas.points_from_xy(cols["X"], cols["Y"]).

Let’s explore the points dataset that we loaded above.

pts.info()<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 18399 entries, 0 to 18398

Data columns (total 16 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 price 18399 non-null object

1 price_usd 18399 non-null float64

2 log1p_price_usd 18399 non-null float64

3 accommodates 18399 non-null int64

4 bathrooms 18399 non-null object

5 bedrooms 18399 non-null float64

6 beds 18399 non-null float64

7 neighbourhood 18399 non-null object

8 room_type 18399 non-null object

9 property_type 18399 non-null object

10 WiFi 18399 non-null object

11 Coffee 18399 non-null object

12 Gym 18399 non-null object

13 Parking 18399 non-null object

14 km_to_retiro 18399 non-null float64

15 geometry 18399 non-null geometry

dtypes: float64(5), geometry(1), int64(1), object(9)

memory usage: 2.2+ MBpts.head()| price | price_usd | log1p_price_usd | accommodates | bathrooms | bedrooms | beds | neighbourhood | room_type | property_type | WiFi | Coffee | Gym | Parking | km_to_retiro | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $60.00 | 60.0 | 4.110874 | 2 | 1 shared bath | 1.0 | 1.0 | Hispanoamérica | Private room | Private room in apartment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.116664 | POINT (-3.67688 40.45724) |

| 1 | $31.00 | 31.0 | 3.465736 | 1 | 1 bath | 1.0 | 1.0 | Cármenes | Private room | Private room in apartment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5.563869 | POINT (-3.74084 40.40341) |

| 2 | $60.00 | 60.0 | 4.110874 | 6 | 2 baths | 3.0 | 5.0 | Legazpi | Entire home/apt | Entire apartment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3.048442 | POINT (-3.69304 40.38695) |

| 3 | $115.00 | 115.0 | 4.753590 | 4 | 1.5 baths | 2.0 | 3.0 | Justicia | Entire home/apt | Entire apartment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.075484 | POINT (-3.69764 40.41995) |

| 4 | $26.00 | 26.0 | 3.295837 | 1 | 1 private bath | 1.0 | 1.0 | Legazpi | Private room | Private room in house | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.648058 | POINT (-3.69011 40.38985) |

1.2.2 Lines

Assuming you have the file locally on the path ../data/:

lines = geopandas.read_file("../data/arturo_streets.gpkg")lines.info()<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 66499 entries, 0 to 66498

Data columns (total 9 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 OGC_FID 66499 non-null object

1 dm_id 66499 non-null object

2 dist_barri 66483 non-null object

3 average_quality 66499 non-null float64

4 population_density 66499 non-null float64

5 X 66499 non-null float64

6 Y 66499 non-null float64

7 value 5465 non-null float64

8 geometry 66499 non-null geometry

dtypes: float64(5), geometry(1), object(3)

memory usage: 4.6+ MBlines.loc[0, "geometry"]Challenge: Print descriptive statistics for population_density and average_quality.

1.2.3 Polygons

Assuming you have the file locally on the path ../data/:

polys = geopandas.read_file("../data/neighbourhoods.geojson")polys.head()| neighbourhood | neighbourhood_group | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Palacio | Centro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.70584 40.42030, -3.70625 40... |

| 1 | Embajadores | Centro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.70384 40.41432, -3.70277 40... |

| 2 | Cortes | Centro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.69796 40.41929, -3.69645 40... |

| 3 | Justicia | Centro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.69546 40.41898, -3.69645 40... |

| 4 | Universidad | Centro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.70107 40.42134, -3.70155 40... |

polys.query("neighbourhood_group == 'Retiro'")| neighbourhood | neighbourhood_group | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Pacífico | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.67015 40.40654, -3.67017 40... |

| 14 | Adelfas | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.67283 40.39468, -3.67343 40... |

| 15 | Estrella | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.66506 40.40647, -3.66512 40... |

| 16 | Ibiza | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.66916 40.41796, -3.66927 40... |

| 17 | Jerónimos | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.67874 40.40751, -3.67992 40... |

| 18 | Niño Jesús | Retiro | MULTIPOLYGON (((-3.66994 40.40850, -3.67012 40... |

polys.neighbourhood_group.unique()array(['Centro', 'Arganzuela', 'Retiro', 'Salamanca', 'Chamartín',

'Moratalaz', 'Tetuán', 'Chamberí', 'Fuencarral - El Pardo',

'Moncloa - Aravaca', 'Puente de Vallecas', 'Latina', 'Carabanchel',

'Usera', 'Ciudad Lineal', 'Hortaleza', 'Villaverde',

'Villa de Vallecas', 'Vicálvaro', 'San Blas - Canillejas',

'Barajas'], dtype=object)1.3 Surfaces

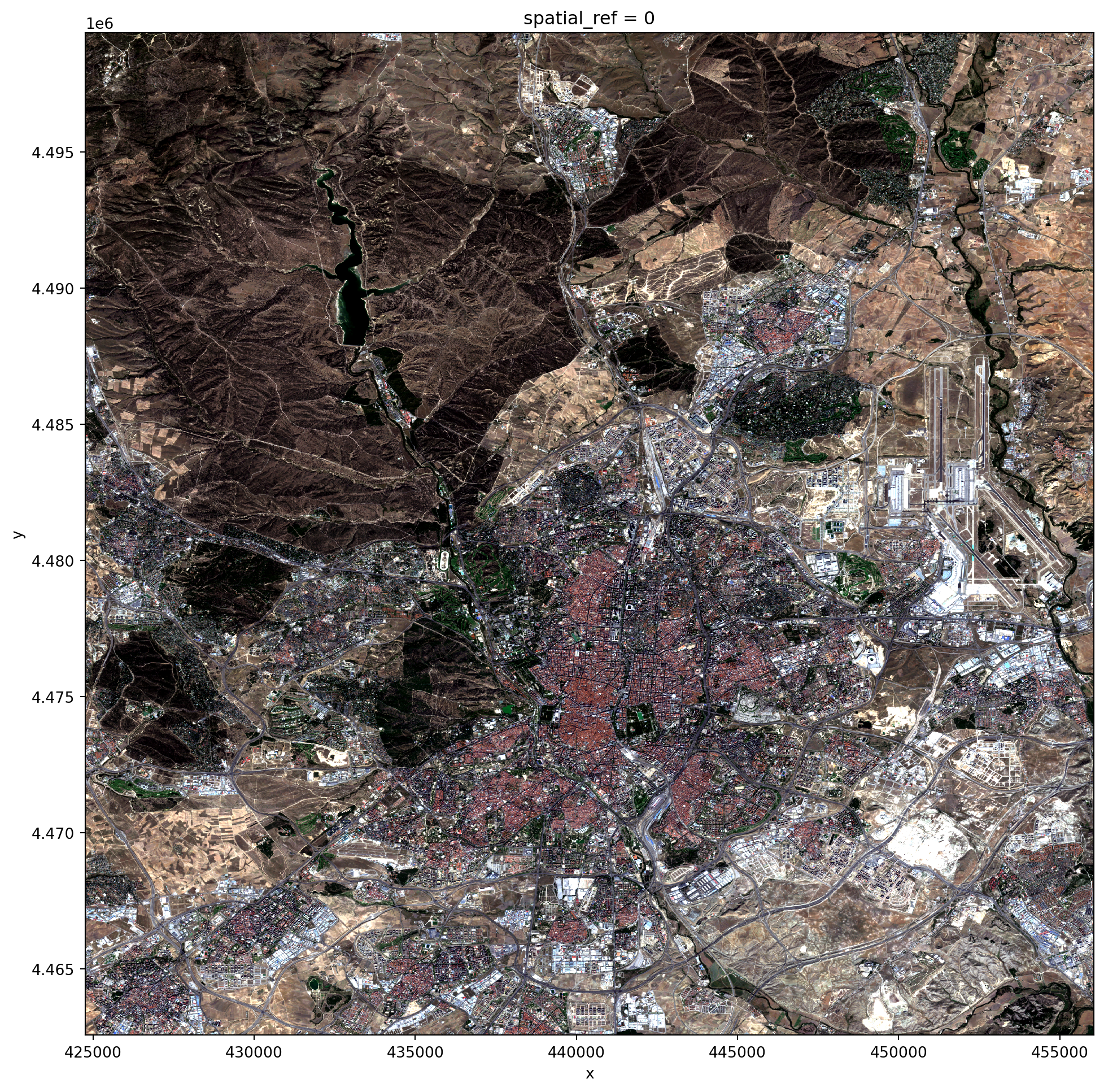

Assuming you have the file locally on the path ../data/:

sat = rioxarray.open_rasterio("../data/madrid_scene_s2_10_tc.tif")sat<xarray.DataArray (band: 3, y: 3681, x: 3129)>

[34553547 values with dtype=uint8]

Coordinates:

* band (band) int64 1 2 3

* x (x) float64 4.248e+05 4.248e+05 4.248e+05 ... 4.56e+05 4.56e+05

* y (y) float64 4.499e+06 4.499e+06 ... 4.463e+06 4.463e+06

spatial_ref int64 0

Attributes:

AREA_OR_POINT: Area

scale_factor: 1.0

add_offset: 0.0sat.sel(band=1)<xarray.DataArray (y: 3681, x: 3129)>

[11517849 values with dtype=uint8]

Coordinates:

band int64 1

* x (x) float64 4.248e+05 4.248e+05 4.248e+05 ... 4.56e+05 4.56e+05

* y (y) float64 4.499e+06 4.499e+06 ... 4.463e+06 4.463e+06

spatial_ref int64 0

Attributes:

AREA_OR_POINT: Area

scale_factor: 1.0

add_offset: 0.0sat.sel(

x=slice(430000, 440000), # x is ascending

y=slice(4480000, 4470000) # y is descending

)<xarray.DataArray (band: 3, y: 1000, x: 1000)>

[3000000 values with dtype=uint8]

Coordinates:

* band (band) int64 1 2 3

* x (x) float64 4.3e+05 4.3e+05 4.3e+05 ... 4.4e+05 4.4e+05 4.4e+05

* y (y) float64 4.48e+06 4.48e+06 4.48e+06 ... 4.47e+06 4.47e+06

spatial_ref int64 0

Attributes:

AREA_OR_POINT: Area

scale_factor: 1.0

add_offset: 0.0Challenge: Subset sat to band 2 and the section within [444444, 455555] of Easting and [4470000, 4480000] of Northing.

How many pixels does it contain?

What if you used bands 1 and 3 instead?

1.4 Visualisation

You will need version 0.10.0 or greater of geopandas to use explore.

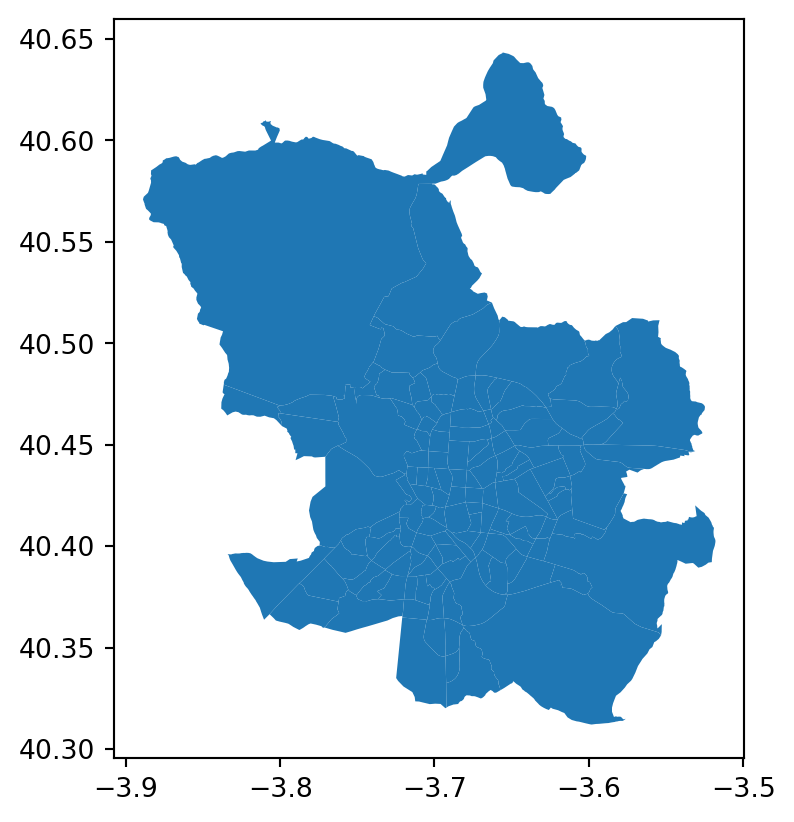

polys.explore()fig, ax = plt.subplots()

polys.plot(ax=ax)

plt.show()

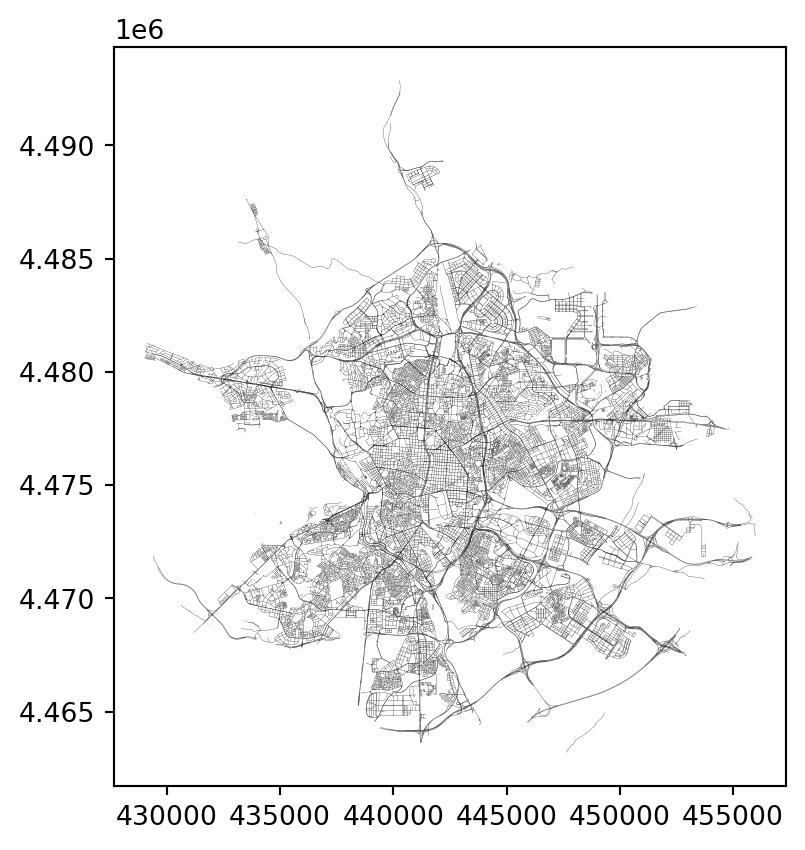

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

lines.plot(linewidth=0.1, color="black", ax=ax)

#contextily.add_basemap(ax, crs=lines.crs)

plt.show()

See more basemap options here.

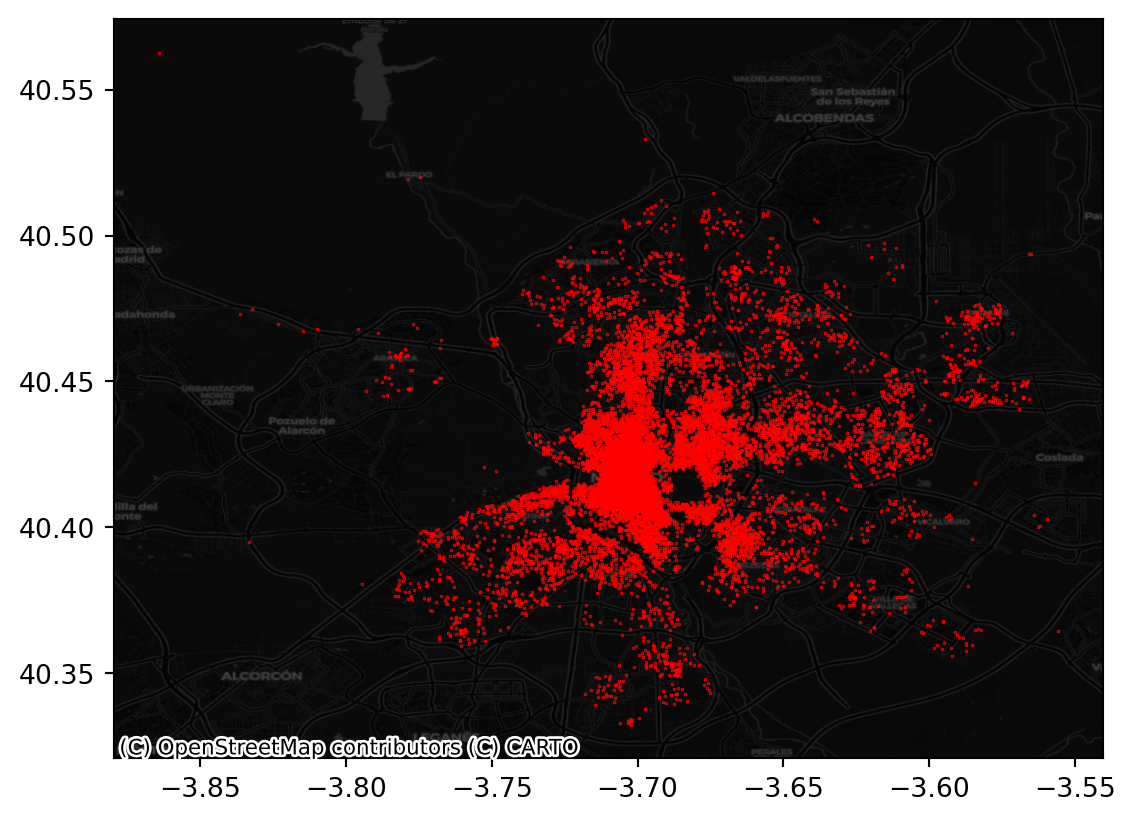

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

pts.plot(color="red", figsize=(12, 12), markersize=0.1, ax=ax)

contextily.add_basemap(

ax,

crs = pts.crs,

source = contextily.providers.CartoDB.DarkMatter

)

plt.show()

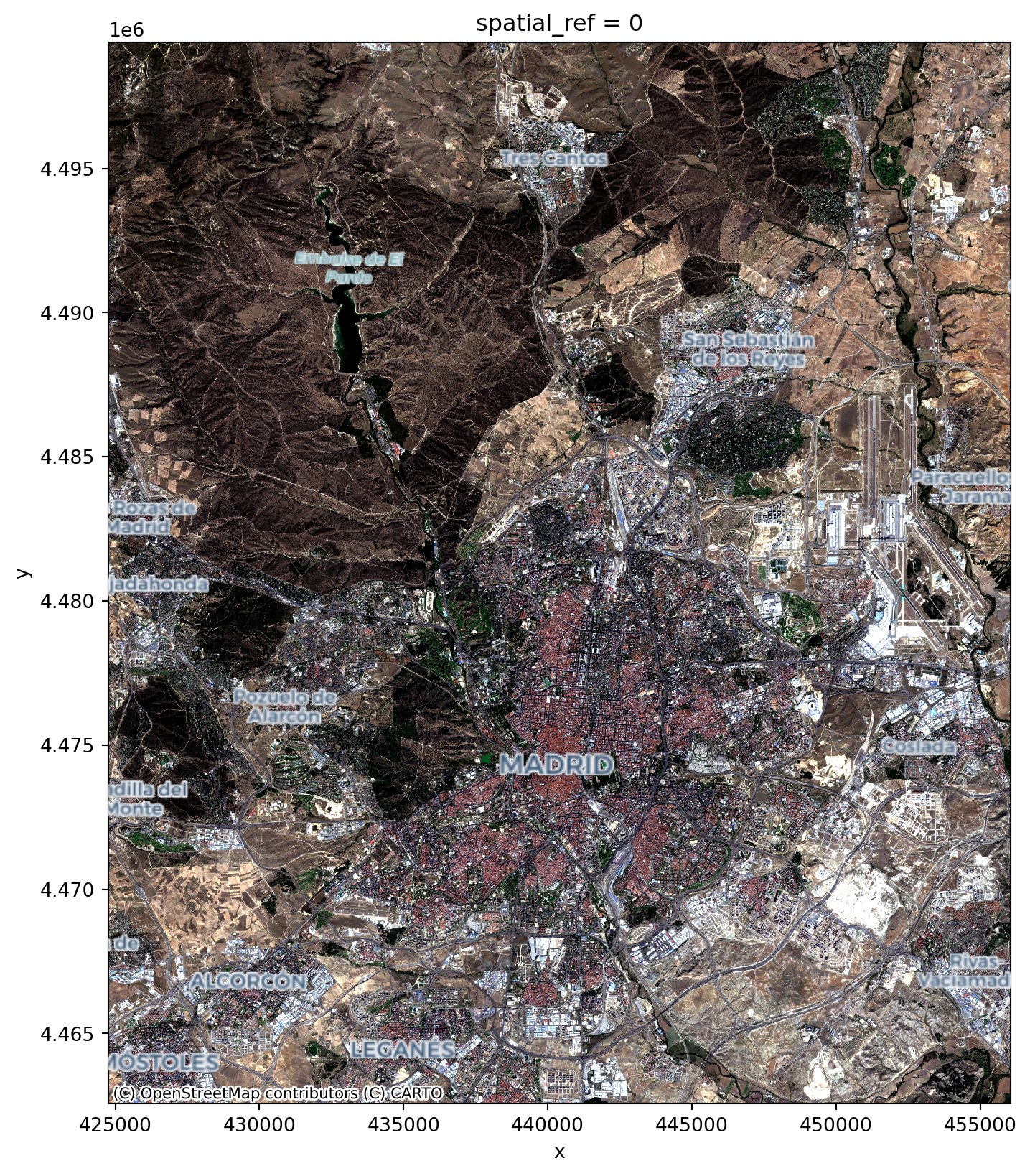

sat.plot.imshow(figsize=(12, 12))

plt.show()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

sat.plot.imshow(ax=ax)

contextily.add_basemap(

ax,

crs=sat.rio.crs,

source=contextily.providers.CartoDB.VoyagerOnlyLabels,

zoom=11,

)

plt.show()

Challenge: Make three plots of sat, plotting one single band in each.

1.5 Spatial operations

1.5.1 (Re-)Projections

pts.crs<Geographic 2D CRS: EPSG:4326>

Name: WGS 84

Axis Info [ellipsoidal]:

- Lat[north]: Geodetic latitude (degree)

- Lon[east]: Geodetic longitude (degree)

Area of Use:

- name: World.

- bounds: (-180.0, -90.0, 180.0, 90.0)

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: Greenwichsat.rio.crsCRS.from_epsg(32630)pts.to_crs(sat.rio.crs).crs<Projected CRS: EPSG:32630>

Name: WGS 84 / UTM zone 30N

Axis Info [cartesian]:

- [east]: Easting (metre)

- [north]: Northing (metre)

Area of Use:

- undefined

Coordinate Operation:

- name: UTM zone 30N

- method: Transverse Mercator

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: Greenwichsat.rio.reproject(pts.crs).rio.crsCRS.from_epsg(4326)# All into Web Mercator (EPSG:3857)

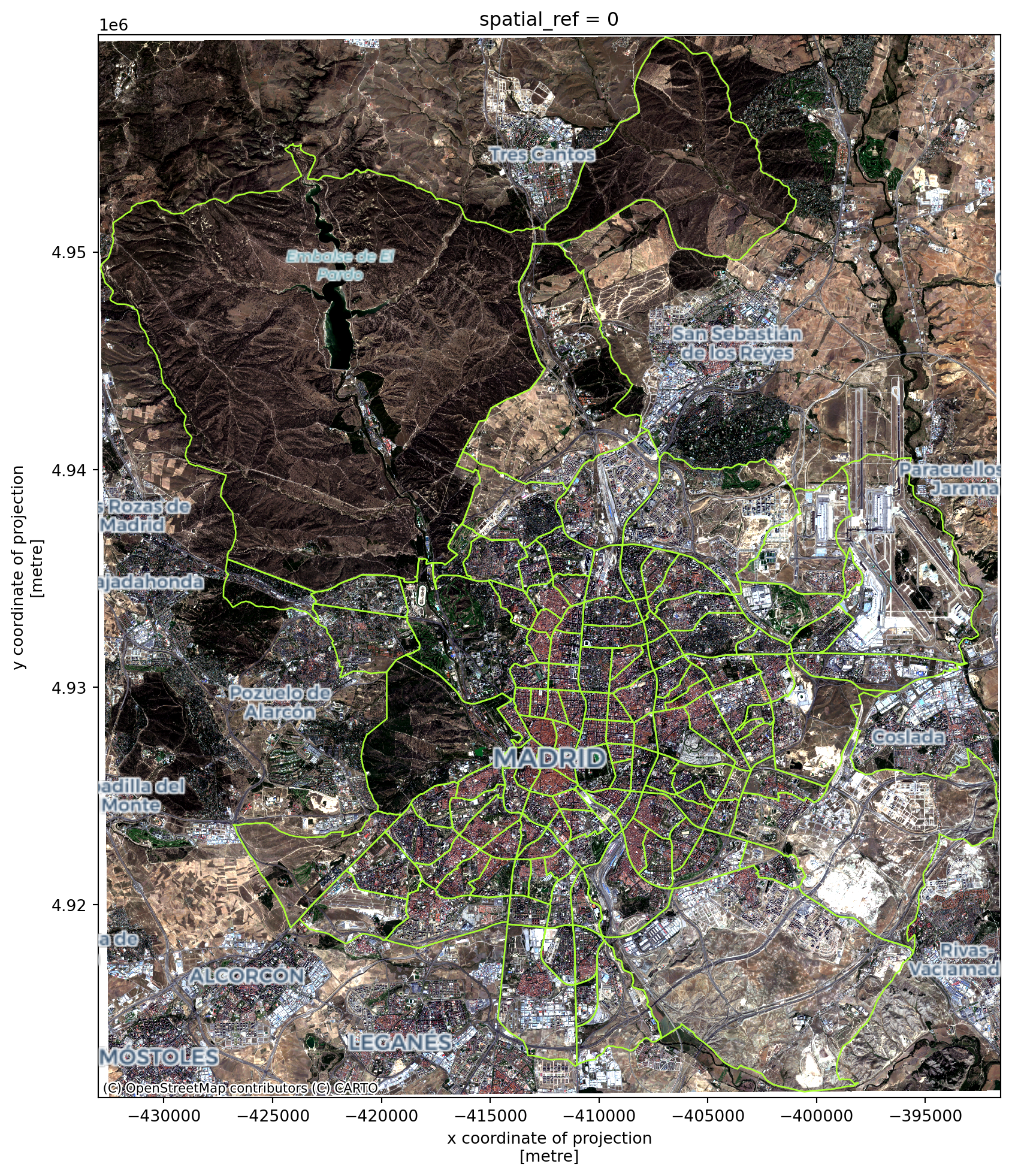

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(12, 12))

## Satellite image

sat.rio.reproject(

"EPSG:3857"

).plot.imshow(

ax=ax

)

## Neighbourhoods

polys.to_crs(epsg=3857).plot(

linewidth=1,

edgecolor="xkcd:lime",

facecolor="none",

ax=ax

)

## Labels

contextily.add_basemap( # No need to reproject

ax,

source=contextily.providers.CartoDB.VoyagerOnlyLabels,

)

plt.show()

1.5.2 Centroids

Note the warning that geometric operations with non-projected CRS object result in biases.

polys.centroid/var/folders/_n/krcxvsq92k7bdd1nfpk3_9c00000gn/T/ipykernel_7098/2101097851.py:1: UserWarning:

Geometry is in a geographic CRS. Results from 'centroid' are likely incorrect. Use 'GeoSeries.to_crs()' to re-project geometries to a projected CRS before this operation.

0 POINT (-3.71398 40.41543)

1 POINT (-3.70237 40.40925)

2 POINT (-3.69674 40.41485)

3 POINT (-3.69657 40.42367)

4 POINT (-3.70698 40.42568)

...

123 POINT (-3.59135 40.45656)

124 POINT (-3.59723 40.48441)

125 POINT (-3.55847 40.47613)

126 POINT (-3.57889 40.47471)

127 POINT (-3.60718 40.46415)

Length: 128, dtype: geometryIt is therefore important to re-project these geometries to a projected crs such as we did with with pts before.

polys = polys.to_crs(sat.rio.crs)Now, we can compute centroids without warnings:

polys.centroid0 POINT (439425.451 4474112.019)

1 POINT (440404.977 4473418.085)

2 POINT (440887.707 4474036.547)

3 POINT (440909.920 4475014.820)

4 POINT (440028.666 4475245.024)

...

123 POINT (449860.280 4478601.086)

124 POINT (449382.527 4481695.863)

125 POINT (452661.832 4480754.248)

126 POINT (450929.735 4480608.573)

127 POINT (448523.423 4479452.348)

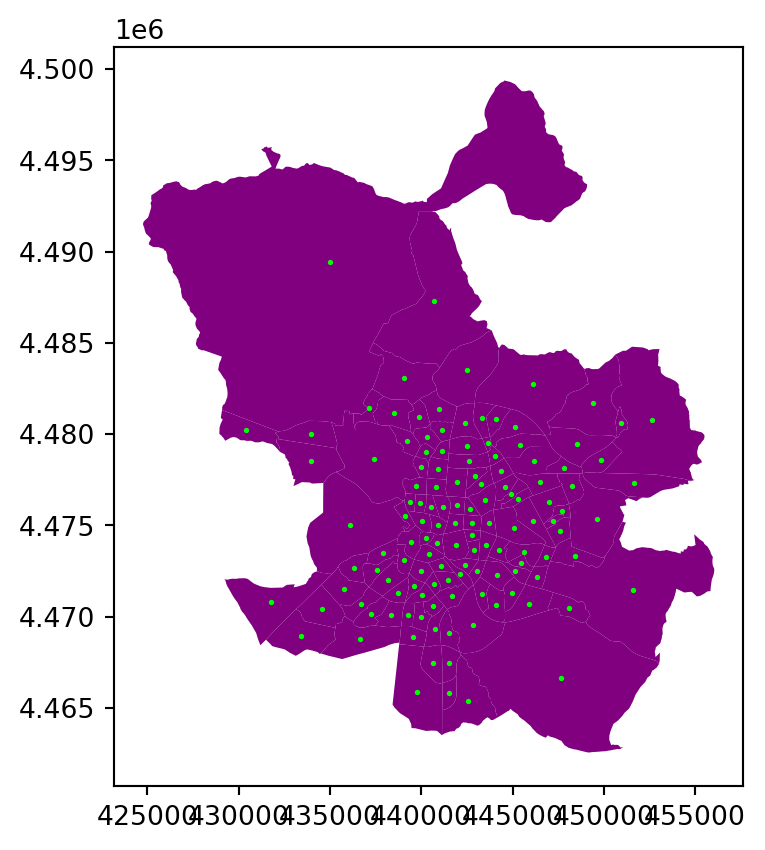

Length: 128, dtype: geometryfig, ax = plt.subplots()

polys.plot(color="purple", ax=ax)

polys.centroid.plot(

ax=ax, color="lime", markersize=1

)

plt.show()

1.5.3 Spatial joins

More information about spatial joins in geopandas is available on its documentation page.

Let’s ensure that the geometries we are looking to join are in the same projection.

lines = lines.to_crs(polys.crs)sj = geopandas.sjoin(

lines,

polys

)sj.info()<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

Index: 69420 entries, 0 to 66438

Data columns (total 12 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 OGC_FID 69420 non-null object

1 dm_id 69420 non-null object

2 dist_barri 69414 non-null object

3 average_quality 69420 non-null float64

4 population_density 69420 non-null float64

5 X 69420 non-null float64

6 Y 69420 non-null float64

7 value 5769 non-null float64

8 geometry 69420 non-null geometry

9 index_right 69420 non-null int64

10 neighbourhood 69420 non-null object

11 neighbourhood_group 69420 non-null object

dtypes: float64(5), geometry(1), int64(1), object(5)

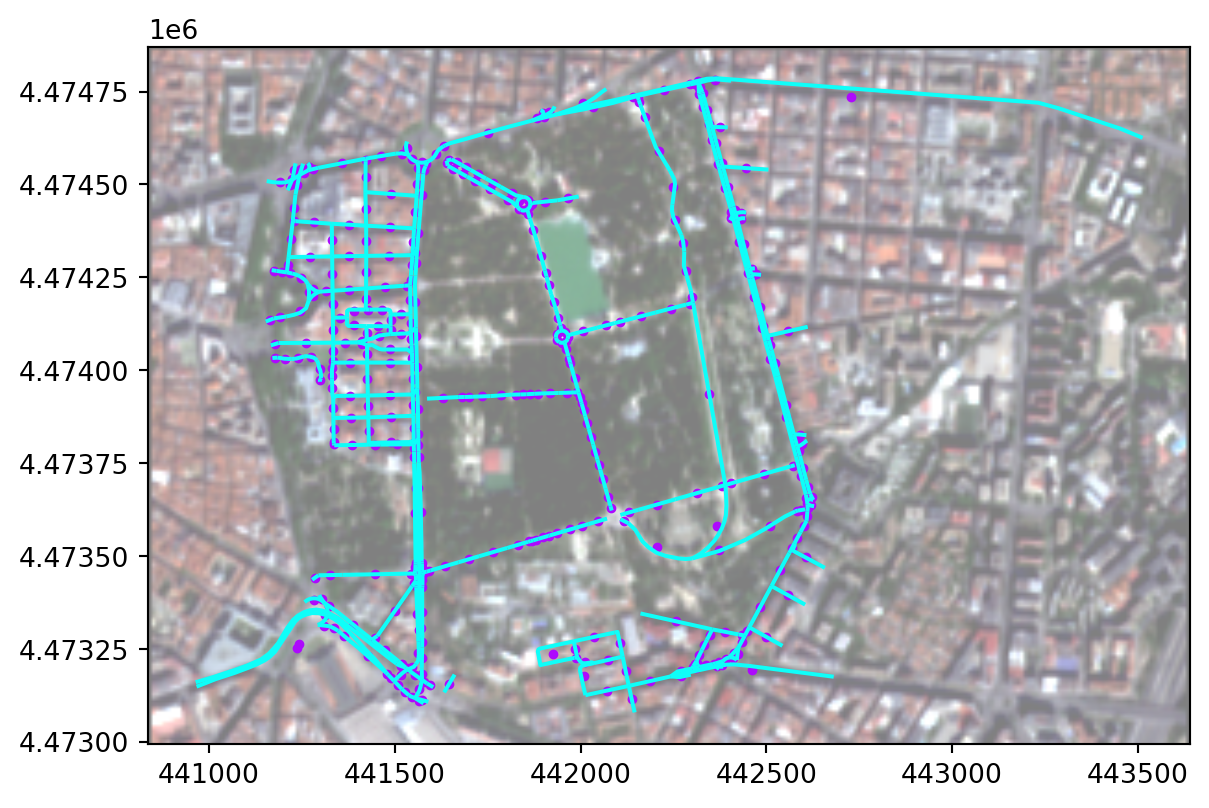

memory usage: 6.9+ MBfig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Subset of lines

sj.query(

"neighbourhood == 'Jerónimos'"

).plot(color="xkcd:bright turquoise", ax=ax)

# Subset of line centroids

sj.query(

"neighbourhood == 'Jerónimos'"

).centroid.plot(

color="xkcd:bright violet", markersize=7, ax=ax

)

# Local basemap

contextily.add_basemap(

ax,

crs=sj.crs,

source="../data/madrid_scene_s2_10_tc.tif",

alpha=0.5

)

plt.show()

sj.info()<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

Index: 69420 entries, 0 to 66438

Data columns (total 12 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 OGC_FID 69420 non-null object

1 dm_id 69420 non-null object

2 dist_barri 69414 non-null object

3 average_quality 69420 non-null float64

4 population_density 69420 non-null float64

5 X 69420 non-null float64

6 Y 69420 non-null float64

7 value 5769 non-null float64

8 geometry 69420 non-null geometry

9 index_right 69420 non-null int64

10 neighbourhood 69420 non-null object

11 neighbourhood_group 69420 non-null object

dtypes: float64(5), geometry(1), int64(1), object(5)

memory usage: 6.9+ MB1.5.4 Areas

To compute areas of polygons, use a projected crs (we already transformed polys to the same projection as sat, which is a projected crs).

areas = polys.area * 1e-6 # Km2

areas.head()0 1.471037

1 1.033253

2 0.592049

3 0.742031

4 0.947616

dtype: float641.5.5 Distances

We can give geopandas.tools.geocode() a string or a set of strings corresponding to addresses. It will geocode it and return a GeoDataFrame of the resulting point geometries

cemfi = geopandas.tools.geocode(

"Calle Casado del Alisal, 5, Madrid"

).to_crs(sat.rio.crs)cemfi| geometry | address | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | POINT (441477.245 4473939.537) | 5, Calle Casado del Alisal, 28014, Calle Casad... |

We can compute the distance between the point for cemfi and the centroids of all the polygons in polys ensuring they both are in the same crs:

polys.to_crs(

cemfi.crs

).distance(

cemfi.geometry

)/var/folders/_n/krcxvsq92k7bdd1nfpk3_9c00000gn/T/ipykernel_7098/176561454.py:3: UserWarning:

The indices of the two GeoSeries are different.

0 1491.338749

1 NaN

2 NaN

3 NaN

4 NaN

...

123 NaN

124 NaN

125 NaN

126 NaN

127 NaN

Length: 128, dtype: float64d2cemfi = polys.to_crs(

cemfi.crs

).distance(

cemfi.geometry[0] # NO index

)

d2cemfi.head()0 1491.338749

1 565.418135

2 278.121017

3 650.926572

4 1196.771601

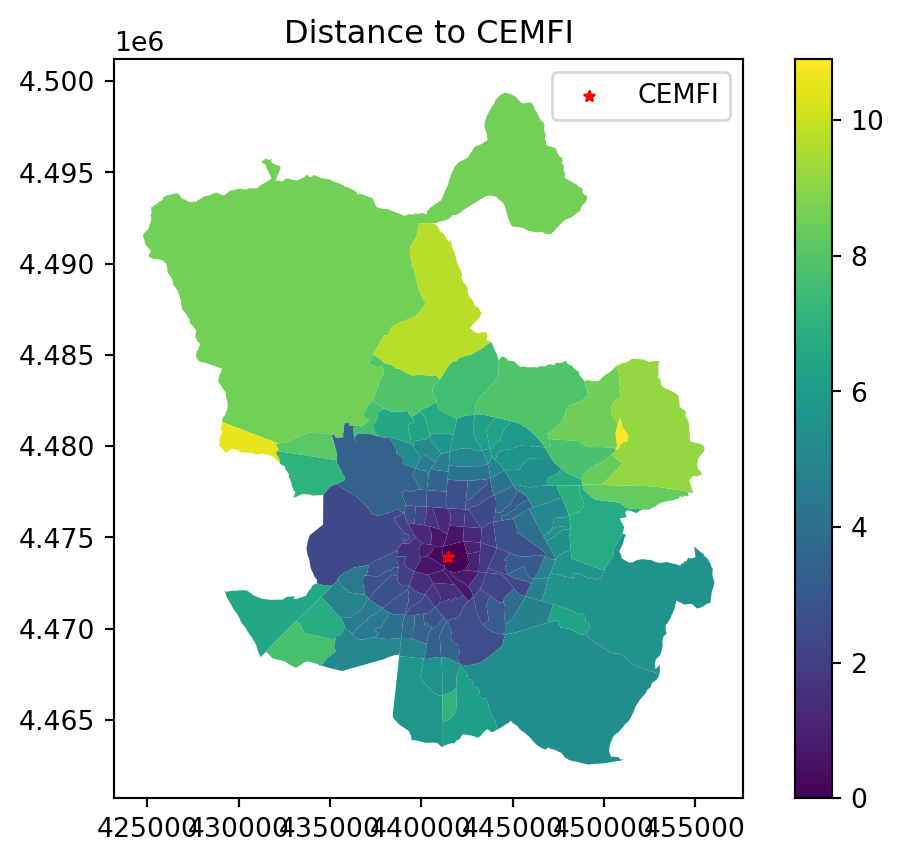

dtype: float64Make a map, colouring the polygons according the the distance of their centroid to cemfi:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

polys.assign(

dist=d2cemfi/1000

).plot("dist", legend=True, ax=ax)

cemfi.to_crs(

polys.crs

).plot(

marker="*",

markersize=15,

color="r",

label="CEMFI",

ax=ax

)

ax.legend()

ax.set_title(

"Distance to CEMFI"

)

plt.show()

1.6 Next steps

If you are interested in following up on some of the topics explored in this block, the following pointers might be useful:

- Although we have seen here

geopandasonly, all non-geographic operations on geo-tables are really thanks topandas, the workhorse for tabular data in Python. Their official documentation is an excellent first stop. If you prefer a book, (McKinney 2013) is a great one. - For more detail on geographic operations on geo-tables, the Geopandas official documentation is a great place to continue the journey.

- Surfaces, as covered here, are really an example of multi-dimensional labelled arrays. The library we use,

xarrayrepresents the cutting edge for working with these data structures in Python, and their documentation is a great place to wrap your head around how data of this type can be manipulated. For geographic extensions (CRS handling, reprojections, etc.), we have usedrioxarrayunder the hood, and its documentation is also well worth checking.